Avoidance, Tolerance & Repair – about business survivability

How designing aircraft to survive in conflict provides some important business lessons on managing risk and resilience.

Going back in time, the basics of international conflict was easier to understand. The context of this blog isn’t important, but the lessons we learn from the story are, as they can be implemented in the resilience and growth of your business.

I was fortunate enough to learn a little about “aircraft survivability and operational effectiveness” during my time in BAE Systems. The background to survivability centres on the point that in conflicts of the past, whoever ruled the air, ruled the conflict. If you had airborne superiority, you controlled the roads (and hence movement / logistics), you had power over outdoor troop movements, and a rapid way to provide support as and when it was needed.

But what happens when the air forces are of similar strength – that is, the aircraft are of similar standard and the air forces are similar in size? The short result is that the side who manages to keep most of their aircraft in the air (or available to be in the air), wins.

So how do we do this? There are three key areas for consideration:

- Battle Damage Avoidance – can the aircraft avoid damage?

- Battle Damage Tolerance – if the aircraft can’t avoid the damage, can they tolerate it?

- Battle Damage Repair – if the aircraft can’t tolerate the damage, how quickly can it be repaired.

That’s one of the reasons military aircraft look so different. They’re each designed with a different role in mind, and take into account the above factors.

Avoidance

Aircraft can avoid battle damage through a number of means such as speed, manoeuvrability, countermeasures (missile jamming, flares, etc) and stealth. Their design and which factors they choose will depend upon the role of the aircraft. An aircraft which has to engage in close quarters with opposition aircraft may choose speed and manoeuvrability to avoid being damaged, whereas an aircraft which can operate from a longer distance may choose stealth to avoid being detected.

Tolerance

Some aircraft operate in a role where damage is inevitable due to it’s role. An example is a ground attack aircraft which has to fly closer to the ground, and as such is within range of a large number of air and ground based threats. In this case, the aircraft has to be able to tolerate as much damage as possible. This is usually achieved by strengthening the aircraft in key areas and protecting the critical components.

Repair

Repair is only even relevant assuming that the aircraft can make it back to an airbase or other point of repair. In such a case, the question is how quickly can the aircraft be recovered to a state where it is of sufficient “value”. I did hear a story once which suggested that a major factor in winning a conflict was how quickly damaged aircraft could be repaired and made airworthy – it was better to have aircraft operating at 50% than no aircraft at all.

So how do we apply these lessons to our businesses?

For anyone who has read my other business blogs, you have have heard me refer to the “high five” – the five key skills required to take your growth business to the next level. These skills are:

Insight – the capacity to gain an accurate and deep understanding of someone or something.

Foresight – the ability to predict what will happen in the future

Acumen – the ability to make quick decisions and good judgements

Adaptability – comes from willingness to change and foresight based on good decision making

Resilience – the ability to weather the tough times

Let’s compare this to the avoidance / tolerance / repair methodology. As we previously mentioned, the first thing that you need is a knowledge of the threats. This is your “business radar”, and comes from your insight. When you have good insight, you can use your foresight and acumen to make the key decisions on what course of action to take. This is the first phase of good risk management – identifying what might go wrong.

It may be that you can keep what you do “under the radar” and operate in a space while your competitors are completely unaware of what you do, and how you do it. It may be that you innovate and adapt quickly enough to stay ahead of the chasing pack (note, adaptability is the fourth of my “high five”. These are your avoidance techniques.

If you can’t avoid your major risks, you’ll need to decide whether (and how) you can tolerate them. If the threat is a competitor reducing costs or releasing a better product, what is your defence? Will you lower your prices? Will you increase your functionality? What is the action that keeps you in the game?

Finally, if the risk delivers a “killer blow” knocking you out of the arena (Covid is a great example here for many businesses) then what will your repair action be? Will you go from personal delivery to online? Will you change your target marketplace? Do you have a “Plan B” which allows you to diversify into a new business or sector, either temporarily or permanently?

What we’re doing here is really risk management, but the whole avoid / tolerate / repair mentality allows you to adopt a slightly different approach which optimises your response strategy. I certainly found that updating my risk registers from the standard “avoid / manage” action to “avoid / tolerate / repair” made them stronger, and made me think more about the key actions in the event of critical failure.

Do you reinforce your strengths or weaknesses?

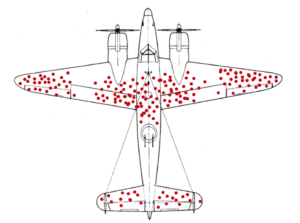

During the second world war, the US military studied surviving aircraft to see where they needed strengthening the most. The plotted the bullet holes on the surviving aircraft, to see where additional armour needed to be added. The diagram is shown below – where would you strengthen the most?

The natural thought is the wingtips and main fuselage. However, the study was totally flawed and prompted the introduction of “survivor bias”. The main problem was that the study only investigated the aircraft that survived. Whilst not possible for obvious reasons, the best study would have been to investigate the aircraft which didn’t survive – to find out which areas really needed strengthening to aid survivability.

Looking at the image again demonstrates one key point – the aircraft that made it back to base had suffered no damage to the engines, cockpit area and the weakest part connecting the main fuselage to the tail. This suggested findings which were the total opposite of the military conclusion – strengthen these areas more, and you’ll increase the survivability of your aircraft, and maintain the size of your squadrons. These new conclusions were implemented and sure enough, the survivability rate increased.

Summary

The message here is to understand your strengths and critical areas. Your weaknesses may not matter – you’re not trying to be a jack of all trades. Know what you’re great at, know what your strengths are and build a fortress around them. Avoid damage, if you can’t avoid it at least you can tolerate it. Then hopefully, you won’t need to repair it.

So, please think about your business survivability plan. What will your strategy be? What happens if your plan A fails, and you need to tolerate, repair or take the next action? Think about your risks and address them. If nothing can go wrong, then by logic alone, everything must go right.